I’ve been fortunate through the years to be able to interview some fascinating people from the worlds of sports, music, and movies. Michael Jordan, Charles Barkley, Rob Reiner, Elton John, and Robert Lamm of the band Chicago have provided some great insights into their chosen professions.

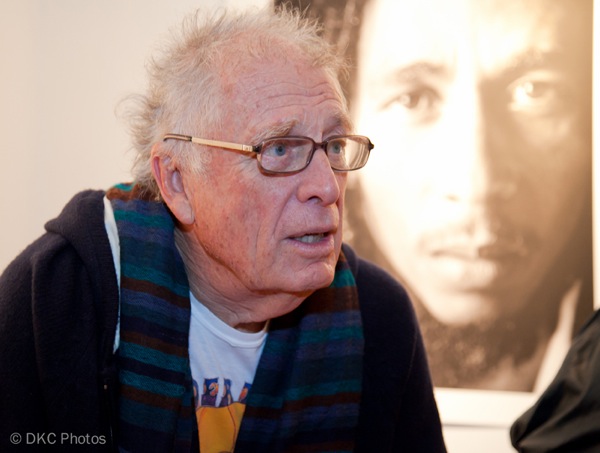

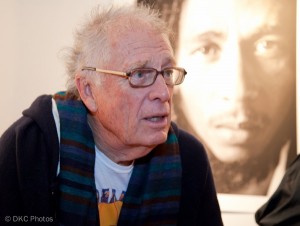

One of my dream interviews had been with Chris Blackwell, the founder of Island Records, and as you will see below, one of the most influential people in the music business (who weren’t performers themselves,) along with Clive Davis and Bill Graham.

Blackwell sold his interest in the record company in 1989, and left it for good in the late 90’s. Since then, he has been busy in the coffee, rum, and tourism industries in his home country of Jamaica, an island of three million people. He owns several of high-end resorts and villas there. One of these is Goldeneye, which was the former home of James Bond author Ian Flemming. It is not as well known, but Blackwell also owns and maintains the Firefly estate, the former home of playwright Noel Coward, whose contents are part of the Jamaica National Heritage Trust. My interest in someday meeting Mr. Blackwell was further solidified after a visit to this site in January.

The stars must have aligned, as the company that markets those resorts brought him to Chicago as part of a presentation to some of the local travel agencies. My wife’s travel agency, where I do a lot of their computer work, graciously allowed me to attend the event, along with some of their key agents.

Arriving early, it wasn’t too hard to spot Mr. Blackwell. Wearing a denim shirt and jeans among a crowd of nicely attired travel agents, he was at the bar, sipping a cup of coffee. This was at 8 AM after all. Beside him was a leather briefcase, with a patch bearing the green, yellow, and black Jamaican emblem. His hair is all white now and thinning, but still cascades downward towards his shoulders. He also has that subtle hint of an English accent mixed with a flat Caribbean affect.

After exchanging some pleasantries, I proceeded to show him a photo I had taken at Firefly, imitating a famous Coward pose in the exact same picture window. That got him in a very engaging mood. Not to be presumptuous, I had cleared things with the marketing manager the day before. We spoke for about ten minutes on the record, before he was whisked away for the presentation. After the event he jetted off to New York, for presumably another one of these events.

He was supremely pleasant, and unassuming, as I excitedly tried to cram as many questions in before he would be called away. So as you read below, I apologize for the seemingly staccato blast of questions on numerous subjects. The last one is by far the most significant, as he more than hints at a return to the music business.

At age 22 you decided to start a record company. What possessed you to do that?

I love music. I was really a fan of music, and there were some people playing at the Half Moon Hotel, where I grew up in Jamaica. I liked the band, and I just thought I’d love to record them. So I asked if I could record them and they said yes. That was that. That’s how I started.

One band, one contract does not make a record company.

No it doesn’t. Well, I loved the process. Because I love music, and in becoming a record producer, you became a little part of the making of the music. I just loved that whole process. After the first record which didn’t do too well, I did another one. That didn’t do well either, but I’d gotten the bug, and I just wanted to do it. The first two records were both jazz albums, then after that, I started recorded singles of what was a whole new music starting in Jamaica, which eventually became reggae.

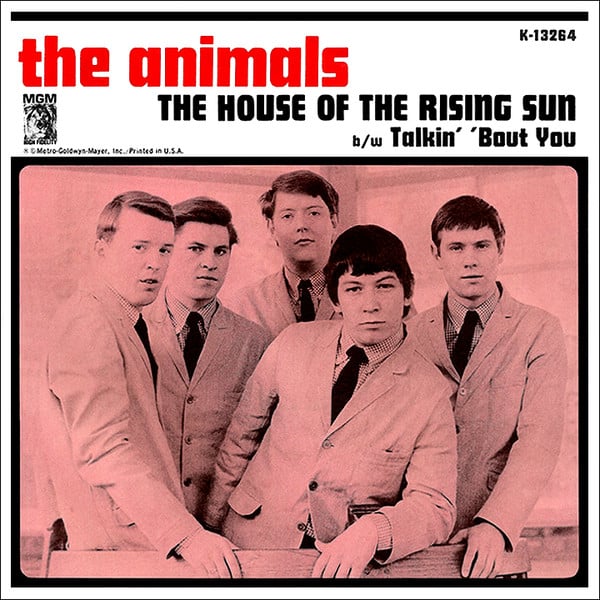

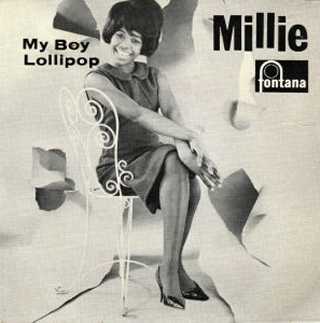

And then along came “My Boy Lollypop” by Millie Smalls…

And then along came “My Boy Lollypop” by Millie Smalls…

“My Boy Lollypop” I produced in England, and it became a huge hit worldwide. It was actually released through a record company in Chicago. A subsidiary of Mercury records called Smash Records. And it went to number two in the United States, and number one in many countries all over the world. But it was a hit everywhere in the world. It sold about seven million copies.

You licensed it out because you couldn’t meet the production demands.

I’ve seen a lot of independent records companies lose their business because they have a hit. Not because they have a string of misses, it’s because they have a hit, and then they can’t supply the demand, and they go into bankruptcy.

How did you meet Steve Winwood?

I was going to a television show with Millie in London and somebody said, “Do you want to come out to some clubs afterwards?” and so Millie and myself went with this guy to a couple of clubs, and at one of the clubs was this young, young, kid singing like Ray Charles on helium. I couldn’t believe it. I just couldn’t believe it. I literally sort of signed him right away.

And then?

His first group was the Spencer Davis Group, and that evolved into Traffic. And Traffic became my favorite band. I love Traffic. They toured a lot. I toured a lot with them. Basically Steve Winwood was the cornerstone of Island Records in a sense because he was so gifted, so talented, that other people wanted to be on the label that he was on. So he was very important in the growth of Island Records.

And that led to groups like King Crimson, ELP, and Jethro Tull. You’re almost responsible for that whole progressive rock scene?

A lot of it, most of it, came through Island.

What do you remember about Ian Anderson and Jethro Tull?

They were unusual. It wasn’t often that you saw a guy standing on one leg, playing the flute as the leader of a band. But he [Anderson] has a tremendous energy and he is a very intelligent guy. They became one of the biggest live bands because they created a lot of excitement. He threw himself into it. He was a tremendous act to watch.

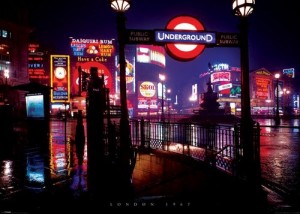

What was London like in its heyday (1967?)

It was incredibly exciting, because there was so much creativity in the air. So if there were three or four people sitting around somebody came up with an idea. And then somebody else may embellish it, and somebody else might add to it, and so forth. Before you know it something was happening and taking place. It was a tremendous sort of confluence of creativity in both music and film at that time.

Who could you see back then in a small venue?

I never saw the Beatles in a club. Eric Clapton came up through the clubs, because he was somebody who loved Chicago blues basically, and modeled his whole playing on Chicago blues stars. So they would play a lot of clubs. Eric took a slow but sure way really, right to the top. The Beatles, The Stones, once people heard them they became huge very quickly. Also The Who and The Kinks. But Eric’s career was one of a musician, rather than a pop star.

You and Clapton both have Bob Marley in common.

Eric singing the Bob Marley song was a very important milestone for Marley’s career, because Eric was like ‘God’ at the time and he was looking for material time, and it was Bob Marley.

What did you see in Bob Marley that made you realize that he was something special?

He was very charismatic, and also when I met him, he had already released quite a lot of records. So not only was he charismatic, he also had proved himself at being a consistent writer.

A lot of record companies rejected U2, yet you didn’t.

I went to see them in a club, and though the music didn’t get to me right away, their passion did. There was something about them, that I felt was just really, really different. Really, really special, and that they were going to make it. Even though I didn’t get their music as it were immediately, because most of the music that I’ve liked has been black music, basically bass and drum being an important part, and they sounded a little sort of ‘rinky dink’ when I first heard them, but I absolutely wanted to do something with them when I saw them. Right afterwards. And another important part was they had a very good manager. Somebody who I thought was a very adult type manager, because rock and roll in many cases, the managers would be one of the pals of the band who didn’t play an instrument. Whereas the manager of U2, Paul McGuiness, was very serious, had a plan, and believed in them completely. So that was an influence too. The main thing was their passion and their intensity, and the fact that there were only about twenty people in the club when I saw them, and you would think there were fifty thousand people, the way they played with a passion and energy, and everything. I can only tell you they are truly unbelievable. There’s never, ever been a band that lasted that long. The same four people.

How about the fact that they still carry the same passion and trumpet a lot of causes?

I think they take a real interest in life and the world, and what’s going on. A lot of people still knock Bono for being too involved and going to these political events Again, never before has anybody from the entertainment business ever had the respect he’s been able to get with heads of government and all these kinds of things. He doesn’t do it because he just wants to hang around. He does it because he has a purpose in each case in making these connections, and charming these people into supporting his various causes. He is a most extraordinary human being. Amazing.

You sold the record company [in 1989.] Why did you do it, and do you miss the music business at all?

I sold it because I didn’t quite see where it was going, and it’s only in the last few months that I’m taking an interest again, and getting back involved in it again. Because I start to see how it’s going to work. It really sort of disintegrated with the digital technology and the bad relationship that record companies started to develop, not just with their acts, but also with the consumers. So I think we’re getting through that whole stage now, because the record companies are getting less important. I think now is an interesting time to be getting back. But of course I’m not a singer; I’m not a performer. I have to bump into somebody who’s really great, who perhaps I can give a hand to, and a direction to making it. So I’m looking again. Let’s put it that way.

Additional links: